Beyond Imagining

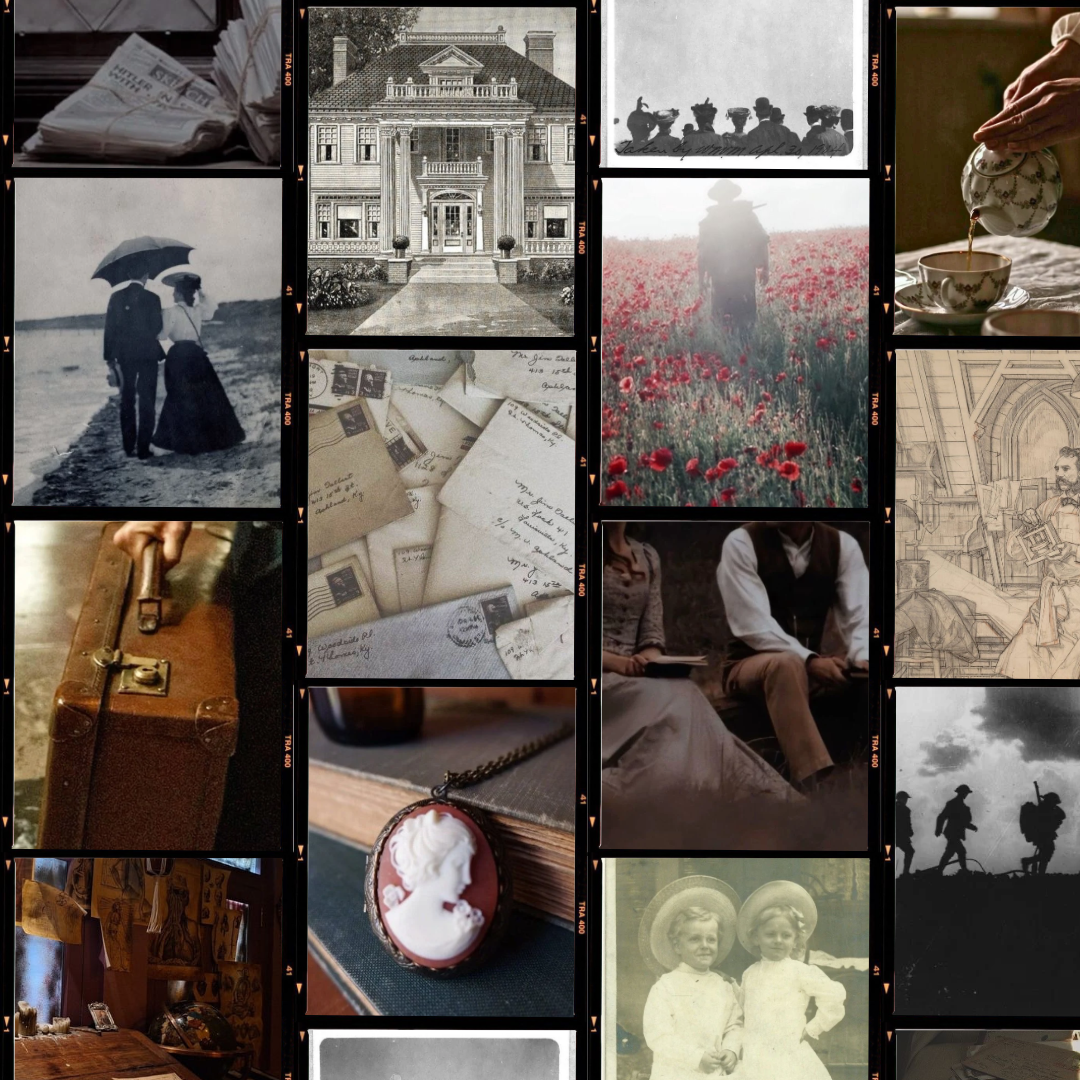

The twins entered the world holding hands. Tommy was first, a burst of crying energy announcing to all his arrival. Jane was not far behind him and, a balm to her brother’s shrieks, mewed softly. That gentle noise fell like a taming spell upon him.

Someone, the family quickly learned, needed to be that soothing spirit for the boy, and who better than the one who’d probably made sure he behaved even in the womb.

They were born into a depressed nation, a crash in the spring pushing them into panic. Cleveland was early into his second presidency, and, had they been old enough, the babies might have let their imaginations run wild about all that was transpiring at the World’s Fair in Chicago. Chicago wasn’t even all that far away, thanks to that ingenious invention of the railway.

Times were changing in ways previous generations would have hardly been able to fathom, a progressive era almost upon them. And, yet, despite shifting expectations and realities, “that Tommy” was growing to be a strange boy, and it didn’t escape the neighbors’ notice.

Wherever did he get those ideas of his? How had he learned all those monstrously big words? What was up there that he seemed to always have his head in the clouds? He’d out-grow these odd notions of invention, surely. They were more like activities of destruction. Whether he intended it that way or otherwise, something always went wrong. Something always was a mess. Thank goodness there was the lovable, little Jane to keep an eye on him in the meantime.

There were days when the boy made an effort at normal activities for someone his age.

“Janey,” he’d said one afternoon, “won’t you play with me?”

Jane, having tea with her doll in the nursery, gestured to an empty chair at her table. “We’d love for you to join us.”

Tea with a silly doll was never any young lad’s idea of play, but he went along with it; it would give him better odds for convincing his sister later to search the woods nearby for specimens.

“Oh but, Tommy, I’ll have to get another cup and saucer for you.”

“I’ll go fetch it.”

Because, in their house, tea time wasn’t for the make-believe beverage. Jane was allowed a tepid pot of water and leaves to steep. Their cook, whose pastries were popular subjects of the children’s daydreams, provided a small tray of sweets. Really, Tommy could have done worse in choosing a means of passing the afternoon away.

Except, as he made his way down to the kitchen, he got to thinking, mind straying as it always did.

What an awful lot of work it was just to retrieve a cup and saucer. The tea would be mostly cold by the time he got back to the nursery. What good would that be? There had to be a better way of going about this, a way to acquire the desired items with less time and manual labor factoring in.

An idea sparked in his mind.

Jane waited patiently for her brother to return so she might serve him tea and a tart. She even refrained from eating the last one because she knew they were his favorite. Patience. Her strongest suit. Borne of necessity, as possessing a temper with a short fuse served no one who, from birth, was paired with a twin such as hers.

Still, Jane was only human. She waited, waited, and waited. Faint, curious noises—crashes and bangs—came to her from elsewhere in the house. When they persisted, she reached the end of her waiting.

She, before rising from her chair, lay her napkin gracefully on her empty plate. Then she left the nursery and followed the disruptive sounds to their source.

They brought her to the back staircase, and she stood at the top, peering down at her brother.

“Whatever are you doing?” she asked.

Tommy, so intently focused on attempting to bring his idea to life, snapped his head up. It was like he’d entirely forgotten other people inhabited this house. “Janey! Would you look at this?”

Though she was looking at the rope he was rigging around the railing, she failed to comprehend what he was trying to accomplish. Add to that the picnic basket and weighty books down on the landing. To be fair, she wasn’t thinking her hardest about figuring it out. No, she was thinking about whether or not she needed to bring this to a stop before Tommy broke something again and their mother found out.

“It’s a pulley system, you see,” he said, like she wasn’t just standing there in contemplative silence. “Why should you have to trot down to the kitchen any time you need an extra cup for tea? Or tea party supplies, in general? Nannie could fill the basket down at the bottom here, and you could stay right up there. Incredible, right?”

In theory, most of Tommy’s ideas were incredible. They’d make everyday activities around the house more convenient, provide an amusing experience, or create something entirely new to the world. It was simply too bad that, in actuality, none of the ideas achieved optimal fruition.

Consider the back stair pulley system. Jane quietly observed her brother tie knots and secure books as counterweights and become more and more excited by the minute. She, in turn, was filled with more and more apprehension.

Because it wasn’t only that they were soon to have a mess on their hands. It was also that she secretly cheered on Tommy’s dreams. He was so smart, so sharp. Surely, he’d get something to work, sooner than later. The defeat that slumped his shoulders in the aftermath of yet another disaster, the sorrow that shaded his eyes, poked right at her little heart. He bounced back quickly, of course, but defeat was defeat. It wasn’t an enjoyable piece of the inventive process.

There was a moment when it seemed the pulley system might just work, and Jane held her breath, afraid that breathing wrong would cause the rope to shift or the books to loosen in their position. Tommy, having come up to stand next to her and set the system in motion from there, got the basket to start up the stairs.

He whooped in excitement and turned to her with bright eyes, a beautiful grin. “Did you see that, Janey? Did you see?”

She nodded, but he was already hurrying down the stairs, saying, “I’m going to try it now with something inside!”

That, apparently, was too much too soon for this pulley prototype.

Tommy had grabbed a ceramic bowl from a side table in the hall and shoved it into the basket. He wouldn’t be convinced he needed to choose a less delicate item. Then he’d raced back up to stand with his sister. Less steady now in the pulling motion, he got ahead of himself and the fancy bowl had to pay the price for it.

Well, he did, too, when the sound of something shattering brought their mother out of her drawing room, embroidery still in her hand. Oh, if Jane could have done something to shield her brother from the exasperated disappointment frowning up at him, she would have.

All she really could do was not leave his side while their mother meted out a punishment—and slip into his room later with the last tart wrapped in her hanky. They were his favorite sweet treat, after all, and she’d saved it expressly for him.

One would think that a boy would tire of being punished for mistakes and mishaps of his own making, especially as they grew in severity.

Confining a child to his room with none of his playthings or tools of experimenting proved ineffective, so it became necessary to hire the strictest of governesses to occupy his every hour. Only, she couldn’t outlast his tendencies and was gone within a fortnight. Taking the switch to his behind settled nothing. What to do, then, with a boy such as Tommy?

It was only after a disastrous attempt at operating a flying machine—spurred on, naturally, by the successes of the Wright brothers—that their father reached a conclusion Jane found too mean to abide.

Said disaster had resulted in a broken leg, for Tommy, and, therefore, countless hours by his bedside keeping him company, for Jane. Secretly, she blamed herself for his injury. When that knowing feeling had bubbled up in her gut, why hadn’t she called him down? She hadn’t told him his efforts would end badly because she didn’t want to snuff out his hope like everyone else.

One evening when she was reading to him from a beloved book of theirs—one of a journey down a yellow brick road—they were interrupted by their father coming in, home from the office. Weary and serious.

He said, “Your mother and I have decided, Thomas, after you’re all healed up, we’re enrolling you in a special school not too far from here. It’s a good school, relatively new but good. They’re in the business of shaping young boys into men of character, and I think that’s what you need, son.”

“But he can’t leave us, father,” Jane tried to protest.

“The paperwork’s already been completed. We should all be grateful a military academy of such repute would consider him worthy of their ranks.”

Jane swung a worried gaze over to her brother, his stricken expression communicating everything she needed to know. The military, even children knew, was an institution of uniformity. Of discipline and rules. Restrictions. Tommy couldn’t be ready for that.

More, though, Jane, despite sometimes tiring of trailing after her brother to make sure he was never in too much trouble, wasn’t ready for him to go. She’d only breathed her first breath of air after he had, and she understood their joint venture into the world was meant to be exactly that. Just what would she do all on her own? And who, at this school, would look after him?

There’d be no tea-time intruders, no mayhem to try and head-off, no stories to share. If she could only be allowed to explain to her father how necessary those things were, maybe he’d write to the academy and tell them there’d been a mistake. She’d promise there’d be no more accidents. She’d figure out a way to get her brother to focus on his lessons. She’d do it. She would, only if he’d be allowed to stay.

That was not to be, and all too soon Tommy’s trunk was packed and he was off to be a pupil at a school that may as well have been in an entirely different country, for how greatly Jane felt the distance between them.

Letters were written, in turns, with regularity, but a piece of paper dotted and dashed with ink was a poor substitution for the spirited boy himself. Letters were what they had, though, so they attended to them with diligence.

And, somehow, Tommy managed to maintain a good standing with his instructors, and only once did a faculty member write to report an incident to their parents. It was early on in the school year, Jane didn’t know the details, and what consequence her brother had to face at that unknown institution was unclear to her, too.

What she learned, when he returned during holiday break, was that sending him off was accomplishing exactly what their father had hoped. Tommy was being shaped into someone else, someone new. That strange spark of his was sputtering, even as he looked the same as ever.

Yet, Jane had never seen him sit so still during mealtimes. She wasn’t used to him being in the house and no odd clanks or thumps sounding from whatever mess he was making. His laughter was no longer so boisterous. He’d grown serious, a terrible fate for a boy.

Jane detected and observed every change, subtle or otherwise. She was ready to sound the alarm, but she knew their parents would only think her silly. Couldn’t she see how beneficial this was for her brother’s maturing? Didn’t she want him to set aside childish whims and ways?

If they’d have posed those questions to her, she would have asked in return: Haven’t I been the one keeping an extra eye on him all these years? I came out of the womb his sister and safe-guard. I failed at preventing that broken leg of his, but I won’t fail now at seeing the breaking of his spirit.

Except, Tommy was sent back for another semester, and there was to be no other preparatory institution for him in his adolescence from then on. Semester after semester piled up with the summer holiday being the only time for the twins to share companionship again.

Jane, helpless to stop her own growing and maturing, never let go of the belief that their parents had gotten it wrong with their son. Over time, her criticism faded a little, but she never stopped thinking that Tommy wasn’t someone to be forced into a different mold. He was to be loved and cherished for the clever mind that he was. Jane could see where all his creativity and curiosity would lead him. Didn’t anyone else? Didn’t anyone connect the dots of how the brothers who inspired Tommy’s attempt at flying were probably just as inquisitive and original in childhood as he’d been? You didn’t make headlines from Kitty Hawk, if it was any other way.

Someday, despite what appeared to be a suppression of his gifts, she knew Tommy would be the first to pilot something of his own, the first to introduce a new contraption to the world. It could be anything, and it would go beyond the current scope of imagination.

She held tightly and dearly to that belief as it came time to attend his graduation and see him off to college.

The night before he left for that East Coast campus, they sat together on the front porch of their childhood home, and she shared that quiet hope she’d long fostered in her heart.

It made him smile, and he turned an affectionate grin her way, saying, “I have often wondered why it was you never tired of my boyish antics, even when they disrupted your life, too. Everyone else was so ready to have me out of their hair, yet you were the only one who made it known you wanted me to stay.”

“You were just a boy. You did nothing wrong. Now you’re grown, and I never hear you speak of your ideas, anymore.”

His grin turned mischievous as he tapped a finger against his temple. “I promise you, they’re all still up here. They’ve been biding their time, and the time is now. Just think of what it’ll be like for me on campus with a proper laboratory.”

Relief found her there in the dark, and it was with great anticipation to hear of all he’d accomplish at college that she waved goodbye in the morning. Her beloved brother was not wholly different. Her beloved brother had found a way to keep that spark of his from sputtering out. She should have known a mind like his wouldn’t have it any other way.

Letters to her now were filled with all he was learning in engineering and chemistry courses. She found it all incredibly interesting, and her grown-up daydreams were full of studying to earn a degree of her own. Had their parents allowed it, she would have been on a campus, too.

Instead, she was out in society. She was fielding suitors and was a student of the art of courtship. Not nearly as exciting as what Tommy was up to, but, then again, he’d always been the twin destined for bolder things.

So, time passed, once more.

Tommy forever had something of interest—a rowdy roommate, graduate school, a serious idea he was brainstorming, an adventure from a city she’d never set foot in—to relay.

Jane’s letters contained inquiries about school yet also about an engagement. She wrote lines about wedding plans and the house her fiancé was having built right down the street for them to live in once they were married. Then, once a newlywed returned from a honeymoon, it was back to the quiet notes of life she’d always penned.

Life stopped being so quiet, though, as a shadow began to loom over the world they inhabited. News from abroad pricked everyone’s ears, made them wonder when this current of events might wash upon their shores. If such a reality might make itself known. American involvement in foreign affairs wasn’t guaranteed.

Then it suddenly became a valid question: Just how many of their boats could be sunk before someone demanded satisfaction?

Before too long, the speculations of war shifted to a Senate vote making a declaration. No longer was it news of conflict and troubles abroad but of homegrown boys joining the fray. Soldiers would no longer be unknown strangers but wearing faces of those she knew.

One so familiar as he sat beside her on the porch of this new house she kept as a lonely wife. First to go had been her husband. Now her brother.

“When do you leave?” she asked, having required a moment to let Tommy’s news sink in.

“Next week,” he said. “I can’t tell you much about my orders, unfortunately.”

“Naturally.”

“They’ve commissioned me as an officer, though. They were very pleased with what my academic aptitude might contribute to the war effort. I thought you’d be proud to know that.”

“Oh, of course, I am, Tommy,” Jane said, looping an arm around him to hold him close. “I’ve always been proud of you.”

Left alone in her empty house, with her best boys off fighting, and worry eating at her mind, Jane hardly knew what to do with herself. If she wasn’t obsessively waiting for each day’s paper with the latest news, she was writing a letter to send love and a piece of home, by way of the post, to unknown lands and stations. Sleepless hours were unbearable, the worst thoughts cropping up then.

Again and again, she’d think of Tommy’s broken leg, as a boy, and the guilt she’d felt over not having prevented it from happening. Why hadn’t she done something? And now why wasn’t she allowed to do something to watch over him better, when she had the nerve and willpower to do so?

Ah, but what was there for any single person to do against weapons of war? Could she deflect a bomb? Could she shield him from a sniper’s bullet? She wasn’t even sure where he was, whether that was out in the field or not.

Her husband came back first, missing an arm and his peace of mind. But he was home, and she could care for him there.

Many months had to pass before she was able to sit, again, on the porch with her brother. She hadn’t known he’d be arriving until he knocked upon her door.

Greeting him, then, on a fine day, an ordinary day, took her breath away because there stood a man wholly changed. There stood a crisp uniform, a somber fellow. Any trace of the beloved boy was gone from Tommy’s features. He was that newly shaped man now, entirely.

It had not taken a father’s strong will nor a strict academy but a great war to have such an effect on him.

Recovering from the shock and surprise, Jane all but hurled herself at him because he was still and forever her brother. “Tommy! Oh, thank goodness!”

She said his name over and over again, like a prayer of gratitude. He let her hold him tightly and dearly. Then they sat together, like so many times before.

Only, this time, so much was different. He was different, and the words he spoke were not those of joyful homecoming.

“What’s troubling you?” she asked.

“There’s too much to tell, Janey,” he said in a low voice. He cleared his throat. “I got back yesterday morning, but I didn’t have the courage to come over and face you until today.”

Perplexed, her brow furrowed and she shook her head. “What are you saying?”

“I can tell you something of my orders now, now that it’s over. I have to tell someone what I’ve done, and it has to be you. Please, don’t push me away, once you know.”

“Have I ever?”

In the moment he needed to gather his thoughts and take a deep breath, Jane held herself taut, mind whirring with possibilities for what he was about to unburden himself of. Goodness gracious, he’d just returned from war. It could be any number of horrific things he’d be about to share.

“They,” he started, “had me working in a developmental lab with the Brits. They gave me bits and pieces of a project to tinker away at, to improve. And do you know what? I was good at it. I’d never been more inspired than when I was working with the tools and equipment they provided us with. And the other men on my team…Brilliant. Absolutely brilliant. We did our jobs so well they decided to bring us in on the whole picture. We’d no longer be working on one, small piece of the bigger puzzle but laboring over it all. And do you know what it was we were working on?”

She shook her head, not wanting to speak.

“Weapons, Janey. The Germans did so much of their dirty work with mustard gas, and our superiors wanted us to turn it back on them. They wanted to revolutionize warfare as we’ve known it, and we helped them achieve that. There has never been anything beautiful about spilling the blood and guts of men, and I’ve played a part in further ensuring that there never will be.”

He needed another moment to consider his thoughts before he gave voice to the crux of his confession. There was no pride in his voice as he said, “I did what was asked of me, and I did it well. Once, when I understood what we were working at, I thought to ask for a change in orders, to do something else that was concerned with being life-giving instead of life-taking. But I didn’t. I couldn’t because I didn’t know if such an opportunity would give me the same freedoms I already had. Every day I was allowed to experiment and bring ideas to life. I could make mistakes and try again the next day. There was no one telling me I had to be different. It was everything I’ve ever wanted, and I could pretend there was nothing bad about it. Nothing bad about figuring out how to put that damn gas inside artillery shells and letting them rain down on men helpless to fight them.

“But there is no pretending. I never went out into the field except once, towards the end. I’d yet seen what destruction my weapons could create. But I have had a hand—two, even—in creating carnage the likes of which the world has never seen. Disfiguration and destruction. Janey, I’ve gotten it so wrong, and I can’t make it right.”

As his final words faded away, Jane knew she needed to offer up some reply. All her life, she’d believed that her brother was destined to live a life among the great inventors of ages past and present. She knew he was capable of making wonders, but this was vastly different. This went beyond imagination, but not how she’d always hoped for him.

What could one do against weapons of war, when you were the one who made and regretted them?

There was nothing to say, no words that would reassure or absolve him.

She watched the face of this broken man, this beloved brother—and she reached for his hand.